Chapter 1: A Pragmatic Philosophy

In general, it gives bits of advice around professionalism and indicates that we, as programmers, can shape our paths.

1. It's your life

We have agency! The industry gives us opportunity to choose our work environment, field and technologies.

You can change your organization or change your organization.

— Martin Fowler

2. The Cat Ate My Source Code

Take responsibility, be accountable, don't be afraid to admit your errors.

Teams should have an environment based on trust where the members can safely speak their mind, present ideas and rely on each other.

Provide options, don't make lame excuses.

Before you tell why something can't be done, listen to yourself and ask if the excuse sounds reasonable. Try to predict the questions coming from the opposite side. Instead of excuses, provide options. Don't say it why it can't be done; explain what can be done to salvage the situation.

Challenges

- How do you react when someone comes to you with a lame excuse?

- When you find yourself saying "I don't know", be sure to follow up with "—but I'll find out".

3. Software Entropy

Software projects will grow over time and they will obviously have tech debt. However, if we keep the tech debt at bare minimum during the growth phase, it'll be easier to work on the project.

Don't live with broken windows.

A single broken window was the reason of the decay of a whole city. Keep your codebase clean and pretty so the up-comers will pay extra attention to not contaminate it.

4. Stone Soup and Boiled Frogs

Stone soup: the story of hungry soldiers who trick villagers to take out their hoardings by telling them they are cooking a stone soup but it becomes more tasty if we add potato, beef, salad, etc...

Be a catalyst for the change.

The story tries to indicate that if you know what needs to be done but not able to convince people with words, try to build something and give a taste of it.

Boiled frogs: if you throw frogs to a boiling water they'll immediately run away but if you put them into cold water and boil them, they won't.

Remember the big picture.

5. Good-enough software

A software is good enough when it satisfies the expectations of its users. Thus, we should involve users during the decision making process and try to keep efficiency in mind.

Great software today is often preferable to the perfect software tomorrow.

6. Your Knowledge Portfolio

Our knowledge is one of the expiring assets. It becomes out of date as new techniques, languages or technologies aspire. We should focus on forming habits to keep ourselves up to date.

Building the portfolio

- Invest regularly: set sample goals, doesn't matter how big they are!

- Diversify: try to become comfortable with different kind of technologies.

- Manage risk: don't go all-in in new tech.

- Buy low, sell high: a bit contra-dictionary to the previous item but remember what happened with React and React Native.

- Review and rebalance

Goals

- Learn at least one language per year

- Read a technical book each month

- Read non-technical books too

- Take classes

- Participate in local user groups and meetups

- Experiment with different environments

- Stay current

Critical Thinking

- Ask the "Five Whys"

- Who does this benefit?

- What's the context?

- When or where would this work?

- Why is this a problem?

7. Communicate

- Know what you want to say

- Know your audience

- Chose your moment

- Choose a style

- Make it look good

- Involve your audience

- Be a listener

- Get back to people

- Keep code and documentation together

Chapter 2: A Pragmatic Approach

Fundamental tips and tricks to follow while approaching problems in the software projects. They are generic concepts that could be applied to any kind of project or company.

8. The Essence of Good Design

Encourage and follow Easier To Change, ETC principle. The wizardry to determine what is easier to change would be achieved in time, but keep your lights on to develop instincts.

9. DRY — The Evils of Duplication

It's one of the buzzwords going around. The take-away from the book is: DRY Is more than code!

DRY is about the duplication of knowledge, of intent. It's about expressing the same thing in two different places, possibly in two different ways.

10. Orthogonality

Two systems are orthogonal if they are designed to be decoupled. When we design the components isolated from each other, we gain productivity and reduce risk.

11. Reversibility

As like everything in this world, the requirements for our software projects might become hard to predict and require lots of changed along the way. To decrease the workload during those inevitable changes, we may hide third-party APIs behind our own abstraction layers and break our code to components, regardless of the architecture and pipeline.

12. Tracer Bullets

We are trying to shoot in the dark and tracer bullets are a way to see our surroundings to become more prepared. In this context,. a-tracer-bullet software would be the simplified version of the almost-production-ready system, which is presentable to the stakeholders and usable during the implementation. They are similar to MVP in some sense.

13. Prototypes and Post-it Notes

They are similar to tracer bullets but without the requirement of being able to work, or production ready quality. Prototypes can even be made of post-it notes or some whiteboard sketches while trying to foresee how the project could be shaped up considering the requirements. While building a prototype, we can ignore correctness, completeness, robustness, and the style. One challenge here is to make sure everyone involved understands the distinction between a prototype and a tracer bullet.

14. Domain Languages

Internal domain languages: RSpec, Phoenix router example

External domain languages: Cucumber (parsed), Ansible (uses YAML)

15. Estimating

Similar to the ETC, estimating is also a skill that develops over time. To become a successful estimator, there are several points we can keep in mind:

- Understand what's being asked: clarify the requirements, discover the side-effects

- Build a mental model of the system: find out the inaccuracies and drawbacks

- Break the model into components: define the interaction between them and assign parameters

- Give each parameter a value: a multiplying factor to be used for each component

- Calculate the answers: don't be surprised if your calculations are weird, they may indicate a missing point or a misunderstood model

- Keep track of your estimating prowess: the only way to get better, ha?

Chapter 3: The Basic Tools

From the importance of using plain text to becoming more comfortable while using shell, keyboard shortcuts, and tips and tricks to debug our bugs.

16. The Power of Plain Text

HTML, JSON, YAML, XML are considered as plain text since they are parseable with a partial knowledge of the format. The actual problem is the text generated by a program is only readable with a similar kind of that program. Backed up by the experience, the text always outlives the software that produced it.

17. Shell Games

A benefit of GUIs is WYSIWYG — what you see is what you get. The disadvantage is WYSIAYG — what you see is all you get.

Explore the capabilities of your shell, customize it, use aliases and command completion.

18. Power Editing

We need to be able to manipulate the text as effortlessly as possible. To do so, we should achieve editor fluency. Avoid repetitive tasks and usage of trackpad/mouse and try to think in "there must be a better way" mindset.

19. Version Control

No matter the size or the scope of the project, team... always use it.

20. Debugging

The origins of "bug" in software word is coming from an actual bug (moth) caught in the computer system back in the days of COBOL. They captured it and dutifully taped to the log book.

Psychology of Debugging

The main purpose should be fixing the problem, not the blame.

A Debugging Mindset

- Turn off your defenses, detach your ego

- Don't panic

- Don't waste time by saying "but, that's impossible", it obviously is

- Beware of myopia when debugging, always try to discover the root cause

Where to Start

- Make sure the project is building without any warnings

- Gather all the relevant data, steps to reproduce, user scenarios

Debugging Strategies

- Failing tests that reproduces bugs: if it takes 15 steps to reproduce a bug, write a failing test for it.

- Regression across releases: compare the diff or switch back and forth to inspect the changes.

- Process of elimination: assume the application code is broken before searching for the cause in OS, the compiler or a thrid-party product.

- Binary chop: use divide and conquer approach for stack traces or logs to narrow down the scope.

- Logging and tracing: Sentry, Crashlytics, etc.

- Rubber ducking: explain what the code supposed to do and the problems to another person (or a rubber duck in your desk)

The Element of Surprise

When we find ourselves surprised by a bug, we must reevaluate the truths we hold dear. If the bug occurred in this piece of code, another piece which relies on the same concepts may also have a problem.

21. Text Manipulation

Learn a text manipulation language (or tool) to make fancy stuff like auto-generating table of contents of this book.

22. Engineering Daybooks

Handwritten notebooks to keep track of what I am working on, take notes on meetings, the things I learnt today and the ideas come up to my mind while dealing with the tasks. Pen and paper helps in a sense since it makes it easier to sketch and scribble.

Chapter 4: Pragmatic Paranoia

Most of the humans perceive world as me vs. the rest, so do we. Programmers also look other's code in a similar way. But, why stop there? We should take it one step further and don't trust our code either. No one writes perfect code, there's no perfect software, everybody is going to die, come watch TV!

23. Design by Contract

Similar to real world agreements between people, the interactions between software modules can also be secured by contracts. The DBC term first proposed by Bertrand Meyer as a part of the Eiffel programming language. Programs should document and verify their claims and it that would lead to predictability in case the contract is violated.

- Preconditions: what must be true in order for routine to be called, an active bank account with positive balance for an outgoing transaction for example.

- Postconditions: what the routine is guaranteed to do, the state of the world when it is executed. The outgoing transaction is created an it's included in the list of transactions for the bank account.

- Class invariants — state: should be updated to represent the changes.

DBC is not a concept we can drop in favor of TDD or defensive programming. It's a complementary approach to increase the confidence.

24. Dead Programs Tell No Lies

Again, leave the "it can't happen" mentality behind and treat errors as a first class citizen in your mind. They usually indicate something very, very bad has happened.

A dead program normally does a lot less damage than a crippled one.

Check out Erlang's supervisor trees approach to capture errors in a propagated places instead of having verbose exception mapping blocks within the subroutines.

25. Assertive Programming

This doesn't apply to the languages I've dealt with but using assertions for exceptions (Java) is actually helpful since they throw traceable exceptions with a recognizable type and message. The book also suggests to keep assertions in code no matter if they're covered with tests since they could be helpful to detect unforeseeable exceptions.

26. How to Balance Resources

Refers to the allocating and deallocating any kind of resources (memory, transactions, threads, network connections, file, timers, etc) that we are consuming in our programs.

The main responsibility to keep in mind is:

Finish what you start.

Nest allocations

Deallocate resources in the opposite orders you allocate them so there won't be any orphans in case of a dependent resource situation.

Always allocate in the same order

If process A wants R1 then R2, process B wants R2 then R1, that may cause a deadlock.

Whoever allocates a resource should be responsible for deallocating it

There was a ruby code example in the book about this. Refer to page 119-120 or put them here.

Balancing and exceptions

Languages with exceptions, or the way handle them can make resource allocation tricky.

let resource

try {

resource = allocateResource()

process(resource)

} finally {

deallocateResource(resource)

}If resource allocation fails and exception is thrown, finally cause will try to deallocate a thing that was never allocated.

const resource = allocateResource()

try {

process(resource)

} finally {

deallocateResource(resource)

}We are safer with this approach and the exception of resource allocation will be propagated to the upper scope.

Use wrappers for resources

We can also write wrappers for resources for allocation, deallocation and check if they are healthy.

27. Don't Outrun Your Headlights

The phrase outrunning the headlights comes from taking turns or going fast with a vehicle the projector of headlines are not able to illuminate the path since it's made for a straight line. The main idea is to take small steps and adjust your next moves based on the feedbacks.

Consider that the rate of the feedback is your speed limit.

Chapter 5: Bend, or Break

Practical approaches for every-day problems that we come across as programmers. Talks about concepts like decoupling, state machines, event handling, thinking programs as data transformers and using configuration.

28. Decoupling

Linking components in a system together is good if you are trying to build a bridge but it is not the best approach while writing software, which we prefer to be flexible since the quality of a software can be measurable by it's easiness to change over time.

Symptoms of coupling:

- Wacky dependencies between unrelated modules

- "Simple" changes in a module requires thousand other changes in unrelated modules

- Developers who are afraid to touch code because they don't know what might be affected

- Meetings where everyone has to attend because no one is sure who will be affected by a change

Train Wrecks

function applyDiscount(customer, order_id, discount) {

const totals = customer.orders.find(order_id).getTotals()

totals.grandTotal = totals.grandTotal - discount

totals.discount = discount

}Problems:

- The top level code needs to know all the chained methods exist and what do they return.

- It'd be better if totals object manages the discount but it's just a container everyone can access and modify. Imagine if we introduce a constraint for maximum discount amount being 40%, it's nearly impossible to manage that.

Tell, don't ask principle states that we shouldn't make decisions based on the internal state of the object and then update the object. It should be capable of doing that itself without breaking the encapsulation and exposing the knowledge all over the system.

function applyDiscount(customer, order_id, discount) {

customer

// TDA: we don't care if orders are list or map, we just want to find it

// orders

// .find(order_id)

.findOrder(order_id)

// TDA: pls apply the discount, I don't care who manages it

// .getTotals()

// .applyDiscount(discount)

.applyDiscount(discount)

}Assuming that customers and orders are one of the top-level concepts of this application, this might be enough.

Law of Demeter

Ian Holland's guidelines to decrease the train wreck. A method defined in C class should only call:

- Other instance methods in C

- Its parameters

- Methods in objects that it creates

- Global variables

The Evils of Globalization

Try to avoid the usage of global data. It makes the code coupled and also you'll realize the setup function on your tests is also a mess. Creating a singleton with fancy methods wouldn't make it OK.

29. Juggling the Real World

Finite state machines

Underrated and very useful way to represent your systems reaction based on the events it receive. The example on page 140 was great.

The observer pattern

Simple way to implement event listeners from a source. One downside is the event source is aware of its listeners so they are theoretically coupled, which is not a big problem if they are in the same context.

Publish / subscribe

More generalized observer pattern which makes the source unaware of its listeners. Events are published to a channel that subscribers are listening. The downside is it can be hard to see what is going on in a system that uses pub-sub heavily.

Reactive programming and streams

Useful for combining multiple sources and creating new streams from the events. We can also generate parallel streams from an event source, then re-combine them into one and etc.

30. Transforming Programming

Think of a program as a transformer that takes an input and generates and output. Based on the requirements, we can streamline the steps to transform the input and isolate them from each other in order to be re-usable, which leads to this tip:

Don't hoard the state; pass it around!

Pipeline operator and kinda railway-oriented approach is shown here with several examples with Elixir. We can choose to handle errors within the transformation itself (return tuple and use overloading) or handle it in the pipeline (bind operator with monadic return values).

Language X Doesn't Have Pipelines

Thinking in transformations doesn't really require it. We can also streamline our steps as intermediate variables to get the job done.

31. Inheritance Tax

Using Inheritance to Share Code

We can use inheritance to add common functionality from a base class to into child classes; User and Product are both subclasses of ActiveRecord::Base.

This is problematic since both the code that uses the child and child itself are coupled to its parent, its parent's parent and so on. It introduces coupling to the codebase.

Using Inheritance to Build Types

We can use inheritance to express the relationship between classes; a Car and a Bicycle are-a-kind-of Vehicle.

This would be problematic once we start introducing more types that can be inherited by Car and Bicycle objects since they can also be Asset, InsuredItem, and so on. It leads to multiple inheritance.

Avoiding Inheritance with Interfaces and Protocols

Instead of creating the base class, we can use interfaces or protocols to specify that a class implements one or more set of behaviors.

Interfaces and protocols give us inheritance without polymorphism.

A Car can implement Drivable, Locatable and Insurable behaviors where a Bicycle is only Drivable and Insurable. We can use a List<Drivable> to store instances of both classes.

Avoiding Inheritance with Delegation

Using inheritance usually overloads the classes with methods which we wouldn't probably expose (gorilla-banana-jungle problem). We can use delegation as an alternative to inheritance in order to perform respective tasks we'd inherit.

#### instead of

class Account < PersistanceBaseClass

end

#### to not expose Framework API to the consumers of Account class

class Account

def initialize(. . .)

@repo = Persister.for(self)

end

def save

@repo.save()

end

end

#### or take one step further to make `Account` class dumber

class Account

## nothing but account stuff

end

class AccountRecord

## wraps the account with the ability to be fetched and stored

endNow the AccountRecord is really decoupled but it would make us to write more boilerplate code for common methods such as find, but we can use mixins and traits for that.

Avoiding Inheritance with Mixins, Traits, Categories, Protocol Extensions, ...

Although the naming varies to language, the idea between mixins is to create a set of functions that can be used to extend a class to use them.

mixin CommonFinders

def find(id) { ... }

def findAll() { ... }

end

class AccountRecord extends BasicRecord with CommonFinders

class UserRecord extends BasicRecord with CommonFinders32. Configuration

In addition to the static configuration that we are mostly familiar with (JSON, YAML, etc), the book also suggest to consider using Configuration-As-A-Service approach in order to make it shareable across multiple applications, editable via a GUI tool and dynamic. This dynamism would help us to register the respective parts of our application to the configuration updates and react to the changes without having to restart the whole application.

Chapter 6: Concurrency

Concurrency, parallelism and temporal coupling

Concurrency is when the execution of two or more pieces of code act as if they run at the same time.

Parallelism is when they do run at the same time.

Temporal coupling happens when our code imposes a sequence on things that is not required to solve the problem at hand.

33. Breaking Temporal Coupling

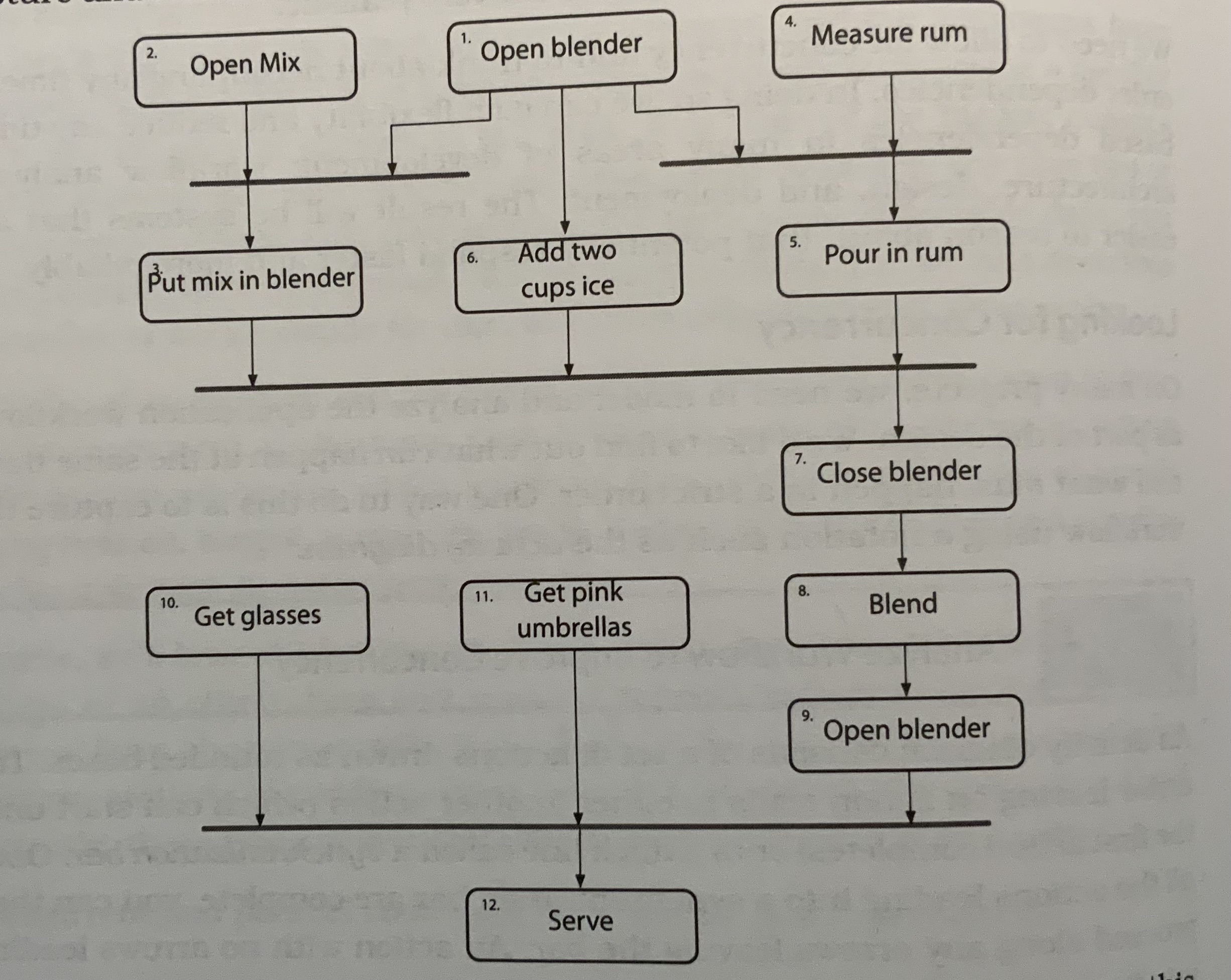

Temporal coupling is about time, which is usually ignored while designing the architecture in the linear mindset. We need to allow for concurrency and think about decoupling in the workflows, and we can use activity diagrams to detect concurrencies and maximize parallelism in the architecture.

Using Activity Diagrams

Identify the opportunities for concurrency and parallelism, then get back to your application. Keep in mind that the activity diagram would only show the opportunities, and exploiting them is up to you. For example, a bartender would need five hands to be able to run the all tasks at once.

34. Shared State is Incorrect State

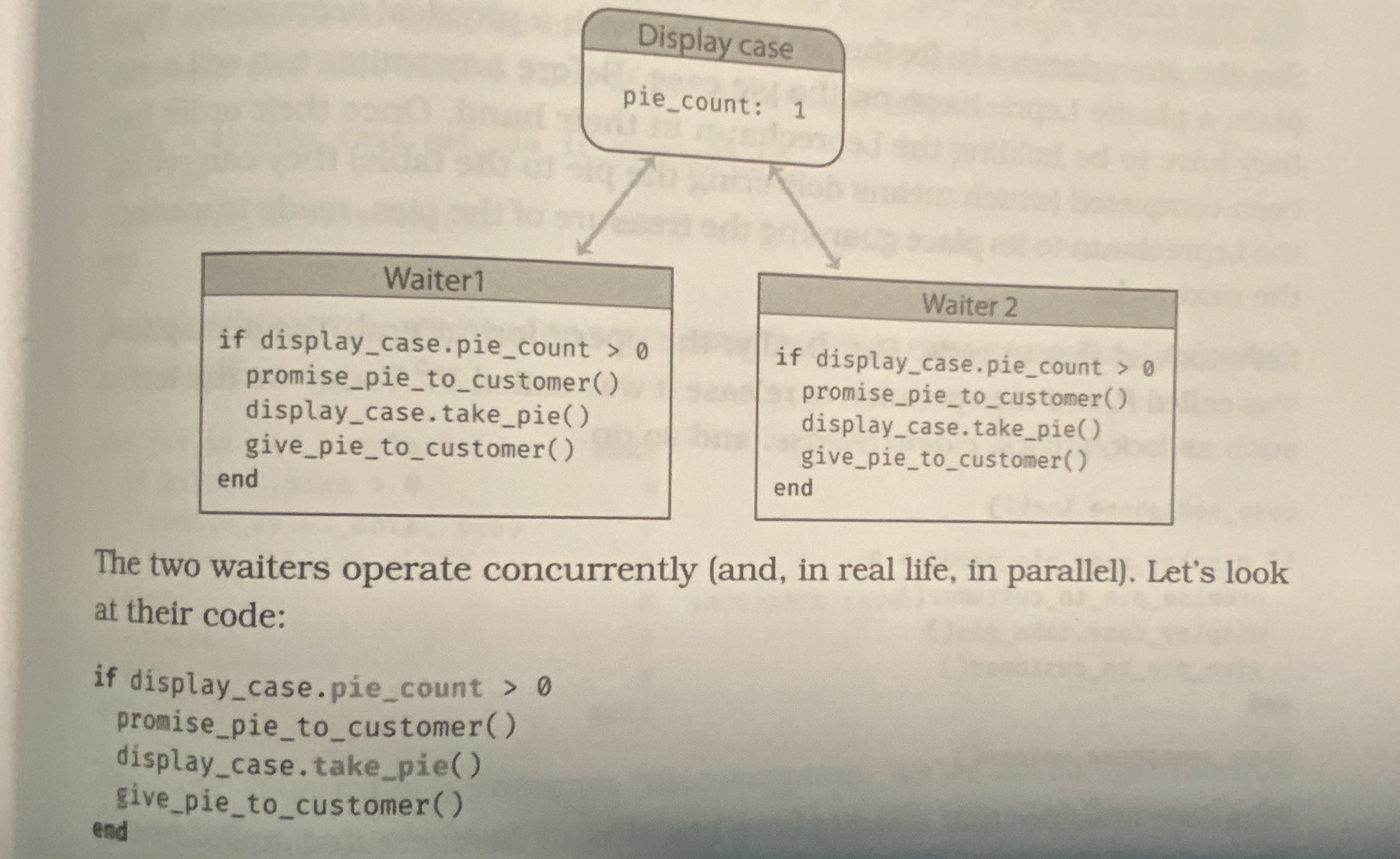

The customer-waiter-pie example starts here. You are in a restaurant (customer A) and asked if they have an apple pie, the waiter (X) looks at the display case and says yes. However, another customer (B) and waiter (Y) has the same conversation in the meantime. Who gets the pie?

Nonatomic updates

Problem: to processes can access and write to the same memory at the same time. Since fetching and updating the pie count is not an atomic operation, the underlying value can change in the middle. So, we can't guarantee who gets the pie.

Atomic updates: semaphores and other forms of mutual exclusion

A semaphore is simply a thing that only one person can own at a time. For the physical pie problem, we can place a plastic Leprechaun and introduce the constraint of holding the Leprechaun in one hand to be able to get the pie. Software representation of this is simply a lock.

#### waiter's logic

case_semaphore.lock()

if display_case.pie_count() > 0

promise_pie_to_customer()

display_case.take_pie()

give_pie_to_customer()

end

case_semaphore.unlock()The problem here is to align everyone on the constraint of using the semaphore, which is on the code level and not really enforcing any constraints.

Atomic updates: make the resource transactional

The lock flow above is not sufficient enough since it delegates the responsibility of protection to the consumer of the resource. We can centralize that check and take the control into the provider's hands by making the resource transactional.

#### API exposed by the provider

def get_pie_if_available()

@case_semaphore.lock()

try {

if @slices.size > 0

update_sales_data(:pie)

return @slices.shift

else

false

end

}

#### update_sales_data may throw, then we'd have a deadlock

ensure {

@case_semaphore.unlock()

}

end

#### waiter's logic

slice = get_pie_if_available()

if slice

#### serve the slice of pie

else

#### say sorrrrry

endAtomic updates: multiple resource transactions

We might say that we have a solution for the pie problem. Now it's the summer season and we add an option to our menu to serve the pie with ice cream. They can still be ordered separately, but the customers prefer to get the combined option. How can we make sure we serve them correctly?

#### waiter's logic

slice = display_case.get_pie_if_available()

scoop = freezer.get_ice_cream_if_available()

if slice && scoop

give_order_to_customer()

endThis wouldn't work because it doesn't ensure the availability of both resources before accessing either of them. We can get the pie but it would be meaningless without the ice cream, and logic to put it back would be another overhaul.

#### waiter's logic

slice = display_case.get_pie_if_available()

if slice {

try {

scoop = freezer.get_ice_cream_if_available()

if scoop

try {

give_order_to_customer()

}

rescue {

freezer.give_back(scoop)

}

end

}

rescue {

display_case.give_back(slice)

}

}A more elegant way to solve this to create another resource called slice_with_ice_cream and move the resource handling to resource itself, as we did for the slice and scoop.

More takeaways

Random failures are often concurrency issues.

Concurrency problems do not only occur for shared memories, they can also be seen while using any kind of shared resources: files, databases, external services, etc.

Mutual exclusion (mutex) term is used for some kind of exclusive access to shared resources, most languages have libraries to support this.

35. Actors and Processes

Actors and processes offers interesting ways implementing concurrency without the burden of synchronizing the state.

An actor is an independent virtual processor that has its own state which is not accessible outside of its context. It waits on the idle state and processes the messages reaching to its mailbox. After the completion, it can consume the queued messages or go back to idle state.

A process is typically a more general-purpose virtual processor, often implemented by the operating system to facilitate concurrency. They are constrained to behave like actors.

Some facts about them:

- There's no orchestration logic that schedules what happens next.

- The only state in the system is held in the messages and in the local state of each individual actor.

- All messages are one way.

- An actor processes each message to completion, and only processes one message at a time.

There is an example of actor system implementation in the book, built with nact.

36. Blackboards

Blackboard stores some facts about the system, many independent actors can be spawned by the changes on that system, work on their processes then add more to the system.

The book describes the blackboard as a real blackboard that we write the details about a criminal case, and detectives as actors who are trying to solve that case.

Blackboard can be used for collective knowledge gathering systems, such as natural language processing, mortgage application lookup and finding an appropriate time for a set of friends to meet in their favorite pizza spot.

Chapter 7: While You Are Coding

Things to keep in mind while we are on it... Instincts, awareness, performance, refactoring and more!

37. Listen to Your Lizard Brain

Lizard Brain → our instincts. Feeling in danger on physical situations is not something made up by our mind, it is actually a response generated by our non-conscious brain. Our lizard brain actually develops over time, by experience and knowledge.

We encounter with the objections from the lizard brain while doing stuff, especially if the page is plain white. First thing to do is to acknowledge that, then take a step back and give time to your brain to organize itself. Do not try to fight or beat it, instead take advantage of that objection to re-think your design, explain it to some other people, and try prototyping instead of solving the problem all together. After you reach a stage that feels like you are in the flow, get rid of that prototype and start over.

It doesn't have to be your code, or just code.

38. Programming by Coincidence

My code doesn't work, no idea why. My code works, no idea why.

How to Program Deliberately

- Always be aware of what you are doing.

- Can you explain code to a junior programmer?

- Proceed from a plan.

- Don't depend on assumptions, rely on reliable things.

- Document your assumptions.

- Don't just test your code, test your assumptions as well.

- Prioritize the effort to spend time on the important aspects, like the blueprint.

- Don't let existing code dictate future code. All code can be replaced if it is no longer appropriate.

39. Algorithm Speed

Big-O notation, common sense for some algorithms:

- Simple loops:

O(n) - Nested loops:

O(n*n) - Binary chop:

O(logn) - Divide and conquer:

O(nlogn) - Combinatoric:

O(c^n)

40. Refactoring

Refactor early, refactor often

Residential building metaphor: architect draws up blueprints, contracts dig the foundation and build the structure, tenants move in live happily after, then they call the building maintenance to fix any problems, or hire some other contractors to improve the conditions.

Refactoring should not change the external behavior of the code, so it is not about adding features. It should aim to make it code easier to change.

When should we refactor?

When we learned something new, understand something better than we did last year, yesterday, or even just a few minutes ago. There are many other things that can be considered as refactoring opportunities:

- Duplication

- Non-orthogonal design

- Outdated knowledge

- Usage

- Performance

How do we refactor?

- Don't try to refactor and add functionality at the same time

- Make sure we have good tests before refactoring, run them as often as possible

- Take short, deliberate steps

41. Test to Code

Testing is not about finding bugs

Your tests will be the first user of your code, and this process would make you think not only as the author. It will also improve the styling while as you will be aiming both for testability and functionality.

TDD cycle

- Decide on a small piece of functionality we want to add.

- Write a test that will pass once it's implemented.

- Run all tests, verify the only one fails is the one we just wrote.

- Write time smallest amount of code needed to get this test pass, and verify the tests now run cleanly.

- Refactor the code.

- Don't exaggerate the TDD cycle, testing the classnames, references and other trivial things do not add value.

A Culture of Testing

- Test first: TDD

- Test during: test while you code

- Test never: gg

Test your software, or your users will

42. Property-Based Testing

A complementary approach to unit-testing. Uses randomly generated data as inputs to our modules in order to observe how would they behave in edge cases, high load, weird inputs.

The failures we come across during property-based tests are often surprises us, and they might indicate bad assumptions.

43. Stay Safe Out There

Basic principles of security:

Minimize Attack Surface Area

The sum of all access points that a system can be compromised.

- Code complexity: less code is more secure

- Input data: always validate input data before running queries and etc

- Unauthenticated services

- Authenticated services: keep the number of authorized users at an absolute minimum. Cull unused, old, or outdated users or services.

- Output data: don't giveaway or try to obfuscate potentially risky information

- Debugging info: don't print the whole stack-trace on production

Principle of Least Privilege

Don't automatically grab the highest permission level such as root or Administrator. Try to accomplish tasks with the minimum privilege.

Secure Defaults

The default settings, interface, configuration on your app should be in the most secure way.

Encrypt Sensitive Data

Don't leave personally identifiable information, financial data, passwords or other credentials in plain text, whether in a DB or some other external file. Don't check in them to version control, manage keys and secrets decoupled from the system as a part of build end deployment.

Maintain Security Updates

Just remember the largest data breaches in history were caused by systems that were behind on their updates.

Common Sense vs. Crypto

The first and foremost rule when it comes to crypto is never do it yourself. It doesn't only apply to cyphering sensitive information, you should also prefer reliable 3rd party providers for the authentication part.

44. Naming Things

- Honor the culture of the language, framework, etc.

- Keep it consistent with the rest of the project.

- Name well, rename when needed. If you can't change the now-wrong name easily, it indicates we got a bigger problem, an Easy-to-Change violation.

Chapter 8: Before the Project

45. The Requirements Pit

Requirements are not really clear on every project, they rarely lie on the surface. They are buried deep beneath layers of assumptions, misconceptions, and politics. Even worse, they don't exist at all.

As programmers, it's one of our qualifications to look for the edge cases, think about the illogical scenarios and help the client to reflect the requirements better. That's what makes our job intellectual and creative. We need to have knowledge about the business itself (sometimes it helps to spend some time in the actual field) and ability to thing about the logical representation when it's reflected by ones and zeroes.

Work with a user to think like a user

Requirements vs. Policy

Some requirements (like privileges) are actually policies which should be implemented as metadata.

Requirements vs. Reality

Short feedback loops plays an extremely important rule on this topic. Brian Eno thought he designed the perfect recording engineer keyboard but all the controls are tied to keyboard and mouse unlike the analog fine-tuning options provided by the classical methods.

Documenting Requirements

This might be a bit waste of time since the clients usually don't read them because they are more into the high-level solution of the problem. However, it'd might be helpful for the developers.

Prefer user stories instead of requirements to visualize the progress better, and more perceivable for stakeholders with different technical backgrounds.

Good requirements are abstract, requirements are not architecture, they are the need. Don't oversimplify, nor over exaggerate.

Maintain a Glossary

One place that defines all the specific terms and vocabulary used in a project.

46. Solving Impossible Puzzles

In order to think "outside of the box", you need to "find the box" first. The secret to solving impossible puzzles is to identify the real constraints.

When faced with an intractable problem, enumerate all the possible avenues before you, no matter how unusable or stupid it sounds. Consider the Trojan horse, you can't bet "through the front door" was the most logical idea, but it worked!

Give credits to your unconscious brain, feed it with your past experience and don't underestimate the power of rubber ducking.

47. Working Together

Start with pair programming, it decreases the trivial approaches and dirty shortcuts, thus improves the quality. Also try mob programming, with those considerations:

- Build the code, not your ego. It's not about who is the brightest. We all had good and bad times.

- Criticize the code, not the person.

- Listen and try to understand others' viewpoints, different is not wrong.

48. The Essence of Agility

The real agility is not following of some rules set on the stone. The true meaning is how you adapt it in your workflows in order to be responsive to change.

- Individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- Working software over comprehensive documentation

- Customer collaboration over contact negotiation

- Responding tho change over following a plan

Keeping the feedback loop efficient, and iterating with small steps gives us the freedom of throwing away our work and starting over in order to reach the desired outcome.

Chapter 9: Pragmatic Projects

49. Pragmatic Teams

Small, cross functional, mostly stable entity of its own, that considers the following items:

No Broken Windows

Teams as a whole should not tolerate broken windows and integrate it as a team practice, thus the newcomers will also adapt it.

Boiled Frogs

Encourage everyone to actively monitor the environment for changes. Stay awake and aware for increased scope.

Schedule Your Knowledge Portfolio

The team should work on more than just new features, it should be serious about improvement and innovation.

- Old systems maintenance

- Process reflection and refinement

- New tech experiments

- Learning and skill improvements

Communicate Team Presence

Great project teams have a distinct personality. People look forward to meetings with them, because they know that they'll se a well-prepared performance that makes everyone feel good.

Know When to Stop Adding Paint

Remember that teams are made of individuals, give each member the ability to shine in their own way. Give them just enough structure to support them and to ensure that the project delivers value.

50. Coconuts Don't Cut It

Know your context, structure and organization before trying to adapt what everyone is doing, or whatever the most popular thing is. Don't hesitate to try things to see what works out for you.

The real goal should be decreasing the delivery time to be continuous, not years, not months, not weeks; hours.

51. Pragmatic Starter Kit

Covers the best practices around version control, continuous delivery, integration, unit testing and so on. One good takeaway from this chapter is; once you found and fix a bug, write tests for it so you make sure it doesn't happen again.

52. Delight Your Users

Ask them how will they know what we've all been successful a month (or a year, or whatever) after this project is done?

53. Pride and Prejudice

- Don't shirk from responsibility, rejoice in accepting challenges.

- Minimize your ego, don't judge other people's work before you are into it.

- Decrease anonymity to prevent sloppiness, mistakes, sloth and bad code.

Postface

As programmers, we have the power to build products which would shape the society. Keep your lights on and don't put your humanity into the second plan.

Ask the following questions to yourself.

- Have I protected the user?

- Would I use this myself?

Recognize when you are doing something against the ideal, and have the courage to say "no!"

Envision the future we could have, and have the courage to create it.